|

One of my favorite Woody Allen movies that few people remember today is about a man named Zelig who takes on, without effort or intention, the qualities and features of the people in whom whose presence he shares at any occasion. So, for example, at a congregational meeting of rabbis, he is suddenly seen donning the Hasidic curls (“payot”) often worn by Orthodox Jewish rabbis. Psychoanalysts couldn’t agree what to make of this phenomenon. “Was it a psychosis or a neurosis?” they debated.

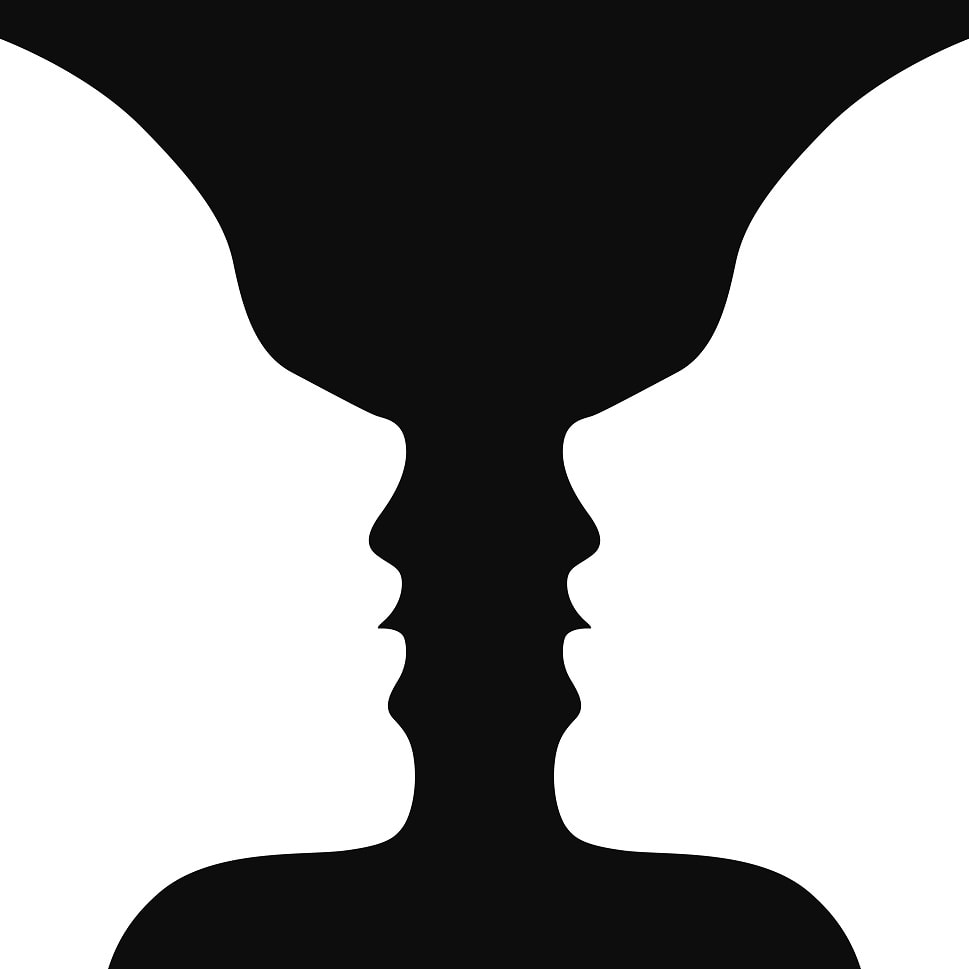

OTTO RANK AND THE CREATIVE WILL In the early days of psychoanalysis, Otto Rank, one of Freud’s original acolytes, and later, adversaries, challenged the efficacy of psychotherapy based on insight and self-knowledge alone in favor of a more active approach (Development of Psychoanalysis, Ferenczi & Rank, 1925). According to Rank, who was especially influenced by existential philosophy, the most fundamental dimension in life is driven by the will to create oneself. This entails the challenge to overcome our deep-seated needs for security to belong and to be accepted by others when they are at the expense of our individuality. By suppressing his will to create himself, Woody Allen’s Zelig could not take on an identity that was his own. An analyst’s task, according to Rank, should be to strengthen the bond between one’s identity and this force of will by affirming the patient’s impulse to act on these creative urges. Relentless probing for self-knowledge about one’s subconscious motives, in Rank’s opinion, was tantamount to “paralysis by analysis” because it weakens the will. When our creative force is suppressed, either through external constraints such as by any social system, family, community, or governmental body that doesn’t tolerate freedom of expression, or by internal constraints, such as through painful introspection that induces guilt or shame, our will becomes directed against ourselves, what Rank called the negative, or counter, will. ORIGINS OF THE NEGATIVE WILL CONCEPT The negative will, as a concept, may be understood as having originated in the work of the 19th century German philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel. Hegel was an “idealist” so he believed that reality is composed entirely of our consciousness, which according to Hegel, is dialectical, or oppositional, in nature. This means that our beliefs, artistic expression, and historical narrative, etc., emerge out of a struggle between opposing viewpoints, such as socialism versus fascism, for example, or a controlling versus laissez-faire approach to childrearing. Fast forward from the sturm und drung of the dawn of romanticism in Hegel’s generation, decades later strains of cynicism and pessimism emerge in the writings of the existentialists such as Friedrich Nietzsche. According to Nietzsche, “all events in the organic world are a subduing, a becoming master” through which “any previous meaning and purpose are necessarily obscured or even obliterated” (On the Genealogy of Morals). In Nietzsche’s mind the virtues of self-sacrifice that are extolled in modern civilization belie the underlying cruelty and resentment that constitute self-sacrifice’s true raison d’etre. Hence Nietzsche was suspicious of the ethics and institutions of modern civilization because their primary purpose has become negative, i.e., toward a suppression of the will of the people. The will of modern civilization founded on resentment is negative, said Nietzsche, inasmuch as it says “no to what is outside.” In other words, rather than originating from an affirmation of self, the slave morality of modern civilization directs its view outside itself with hostility in order to define itself and its reason for being triumphant under the guise of humility. Otto Rank, whose work was heavily influenced by Nietzsche, posited that negative will is manifest in human psychological development both as a function of the natural evolution of the will, an incipient phase of normal development per se, and a dysfunctional state of being in adulthood where one’s natural, creative urge to express oneself is inhibited. As a normal phase of development, negativity may represent the beginnings of a child’s discovery of its own power that stands in necessary opposition to its parents and the greater power of the world around it. One’s sense of self develops, like the artistic concept of negative space, firstly from its “negative” relationship to the world in which it lives before a more creative self can begin to take hold. But the negative will, said Rank, can manifest also in adult life as a “neurosis,” i.e., the self-loathing, self-doubting, anxiety-ridden character whose will is directed against oneself. The neurotic person denies the validity of one's experience of oneself that corresponds to a lack of one's sense of self-worth. APPLICATIONS OF NEGATIVE WILL TO TODAY’S WORLD I. The Study and Treatment of Negative Will in Childhood The concept of negative will has found both theoretical and practical applications to developmental psychology. In the late 19th century, the developmental psychologist, James Mark Baldwin, posited that our sense of self develops in early childhood both through imitation of and opposition against our caretakers, siblings, and others with whom we are most intimately involved at an early age. Gordon Neufeld, the founder of the Neufeld Institute in Vancouver, Canada, is a developmental psychologist who provides training for parents and professionals. According to Neufeld, childhood problems such as excessive shyness and defensive detachment that arise from a child’s oppositional relationship to its parents and authority figures may be addressed with family counseling and training. Neufeld’s training program teaches that the fundamental concepts necessary for healthy child development, what Neufeld calls “The Emergent Self,” depend on fostering a sense of self-efficacy and autonomy, teaching resilience to the finalities that limit one’s power to overcome, and facilitating the capacity to integrate the countervailing motives and concerns that constitute internal conflicts. II. Negative Will in Personality Disorders Negative will also represents a fundamental dimension of identity in adulthood that differentiates personality disorders from a healthier, creative self. In my paper, Negative will, self-image, and personality dysfunction, The Psychoanalytic Review (2009), I proposed that when an individual’s prevailing experience and corresponding behavior are predicated on an adversarial or alienating relationship between self-interest and the interests of others, i.e., the collective interest, dysfunctional patterns of interpersonal relationships will ensue to the detriment of one’s sense of well being and creative potential in life. In my paper, it is explained how each type of personality disorder traditionally classified in modern psychiatry may be explained in accordance with this more philosophically based concept. The purposes of this project are, first, to offer a more coherent model within which the loosely-strung “classification” system of personality disorders has been used, secondly, to establish a more comprehensive framework, specifically philosophy and ethics, by which the dynamics of self-development and personality formation and their problems may be understood, and thirdly, to extend how this concept may apply beyond neuroses to narcissistic disorders. For the narcissist, the negative will is directed outwardly rather than against oneself. For the narcissist, the animus of negative will may manifest as resentment, disdain, distrust, and the need to overpower or constrain the freedom and will of others. III. In Today's World The significance of negative will is not lost to the kinds of problems faced by humanity in this day and age. In a world in which the polemics of culture are straining to their limits, ideas, politics and religious beliefs have taken on a prohibitively dogmatic pitch and tone intolerant of disputation, one that vilifies rather than engages curiosity and openness to the “other.” The so-called authoritarian personality, first studied by Adorno and his associates at Harvard University in the wake of the defeat of fascism after the second world war, emerges from such dogmatic systems. They are invariably characterized by blind fealty to a charismatic ruler and renunciation of one’s personal autonomy and creative potential. Resistance to change born of fear seeks refuge in the familiar. We are now seeing communal bonds and personal identity forged on alliances predicated on these fears. These groups seek to oppose all that threaten to destroy these hollowed traditions as a bulwark against change. The upshot of this is that civilization is increasingly governed by a culture of resentment not unlike that identified in Nietzsche's jeremiad of Western civilization, defined by what we are opposed to rather than by who we can become. The threat we face is to define ourselves by what we stand together in opposition to, acting in deference as slaves to a master, rather than from within our freedom to exercise the capacity to use our judgments and potentials creatively as individuals in open engagement with ideas not necessarily of our own.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Robert Hamm Ph.DPsychologist Archives

June 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed